One Future

MenuEvolution’s origin

A reconfigured history of universal emergence

- Universals

- Issue 3

In the beginning there was no beginning. There was a unified infinity of nothing. Time didn’t pass.

If matter existed it was indistinguishable from pure energy.

PART I

Evolution’s Origin

The main event in this cosmos is not evolution. Evolution is a side effect, almost a tertiary after-thought or accidental by-product of the main event. The main event is something far more ordinary, far more mysterious and possibly far more profound than evolution could ever be. As far as great cosmological explanations for the nature of reality go—the theory of evolution is a charlatan.

In this long-read article I highlight the reason for cosmic emergence and how that reason reconfigures how we can approach innovating meaning and purpose for human being in the third millennium.

In the process of doing this I discuss the semantics of talking about evolution, and talk about the science based views of palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould. This article is also in part a critique of the “Directionalists” and “Evolutionary Spiritualists” and their incorrect arguments for an orthogenic force or “evolutionary impulse” that “drives” evolution forwards—which may be a tad boring, but important, I think. I apologise in advance for that. If you stick with it, hopefully you’ll find this an interesting take on how our cosmos works and the implications for thinking about human being in the third millennium. In doing so I’m attempting to help lay robust foundations for any development of a “spiritual” (in inverted commas because I hate that word), but also scientific view of a cosmos from which we can explore new forms of meaning and purpose in a robust and scalable way.

It’s probably also relevant to mention: whilst I have read a few books on the general topic (mostly referenced here) I’ve done no independent research and I just made most of this up by thinking about things a lot and staring at things in my garden.

IN THE BEGINNING

I thought to start by explaining my general point of view (so far) of what Evolution’s Origin is, then compare this with the views of other commentators.

The main engine of evolution in the cosmos is the ever present freedom that has been a fundamental of existence since the dawn of creation. The growth of the cosmos that is often called Evolution is the virtue of universal creative freedom born of the vastness of spacetime, and a vast multiplicity of matter in what appears to be a cosmos fined tuned for optimal creativity (I’ll come back to this later).

In the beginning there was no beginning. There was a unified infinity of nothing. Time didn’t pass. If matter existed it was indistinguishable from pure energy. Physicists talk of an “infinitely dense point of existence” from which everything emerged. But before that there was nothing at all. The universe as we know it didn’t exist. This infinitely dense point was the starting point of what we call the big bang, but, actually, there was no such thing as a big bang as there was nothing to bang into. Space hadn’t been created yet. That’s why theories of what happened in the first second or so of the cosmos are called “inflation”—because space had to “inflate” into existence for there to be any banging going on. Within less than a second the cosmos expanded from a single point to being millions of light years wide.

Apparently the initial forms of matter were not atoms as we normally know them as the early universe was too hot with too much energy to allow them to settle down into a stable form. This period was known as the dark ages of the early cosmos. There were photons of light but they were essentially unable to travel, caught in a dense plasma of matter. Once the universe cooled significantly, around 300,000 years after the “big bang”, these photons were released in a flash of light as matter condensed into hydrogen, helium and some lithium atoms. Apparently all the matter present in our cosmos is just a small percentage of the original amount—which was mostly wiped out by antimatter during this cataclysmic birthing process.

The formation of particles of matter heralded the advent of “agency” in the cosmos. By agency I mean individuation or individuality, albeit at the beginning, it’s in the most basic of forms—subatomic and atomic particles. But, once there was agency amidst the freedom afforded by time and space, the free creative unfolding that we look back upon and call evolution had definitely begun.

ADJACENT POSSIBILITY

Adjacent possibility is a term invented (to the best of my knowledge) by the thinker and writer Stuart Kauffman [Reference 1] that is exceptionally useful in talking about and understanding creative freedom and evolution. Adjacent possibilities are exactly as they sound: those possibilities that are closest. For example, an atom exists. By virtue of it’s existence it has adjacent possibilities. One adjacent possibility may be that it can combine with another atom and form a molecule—if there is another willing and able atom nearby. If you are sitting quietly in a cafe with a random assortment of people—an adjacent possibility is that you all get together and decide to pile the furniture to one side, remove your clothing and run around in a circle singing the national anthem. Yes, I would agree that’s not likely (at least not where I live) but the point is it’s possible because all the components required are more or less present, making it adjacently possible.

I really love this phrase adjacent possibility, as with two words I believe it ever so simply sums up the complex phenomena of what’s known as self-organisation. (And if you’ve ever tried to read the seminal, but quite impenetrable book by Eric Jantsch, The Self Organising Universe, you’ll understand how important this is!). The so-called free creativity I mention is of course, not so free. There are real system constraints acting on any given agent. For example, an apple on your kitchen table won’t suddenly float upwards (unless your kitchen table is in deep space) because of the Earth’s gravity. In other words, the apple’s adjacent possibilities are it’s real and direct possibilities and won’t include any actions outside of it’s current system constrains, including floating.

This is how free emergence works. When the there is freedom (tick) and agency (tick), adjacent possibilities can be explored. The entire history of emergence in the cosmos has been as the slow but inexorable exploration of adjacent possibilities.

CREATIVITY THRESHOLDS IN COSMIC EMERGENCE

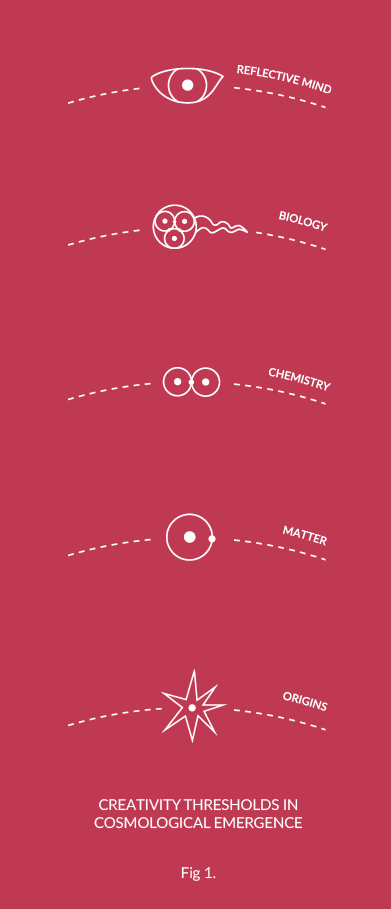

With increasing complexity there are developments in the cosmos’s capacity to be creative. For example: Atoms have few creative options, whilst molecules have far more reactive opportunities. Livings cells have again even more—and so it goes. The cosmos has moved through several of these “creativity thresholds” (Fig 1)—every time it’s ability to be creative has been amplified. I like to think exponentially amplified, but I have no idea of the maths of the probabilities. Simply said as the cosmos crosses these creativity thresholds, the increase in adjacent possibilities is immense at each stage.

For example any Oxygen atom has it’s own set of reactive capacities, but upon inclusion into a CO2 (Carbon dioxide) molecule or a NO3 (Nitrate) molecule, it’s reactive options (adjacent possibilities) are now embedded and subsumed into a new greater “whole” of the molecule it is now in. Carbon dioxide and Nitrate have entirely different natures, thus entirely different adjacent possibilities. The original Oxygen atom has now been part of a creative emergence where it’s inclusion into the adjacent possibilities afforded these new molecules, means there are radically (numerically) more adjacent possibilities than the Oxygen ever had—and it’s involvement has enabled this to take place. The atom has passed trough what I’m calling a “creativity threshold” of possibility, from free atomic creativity (less creative possibilities) to free molecular creativity (more creative possibilities) [Note 1].

As the cosmos has grown there has been increasing agency or individuation—and with increasing agency there are increasing adjacent possibilities. For example a grain of sand has some agency—it can move, it can have chemical reactions, but in very basic ways. A rabbit has far greater agency, it can do more, far more wilfully. With increasing agency there is increasing exploration of options in this ever present freedom. Generally speaking, the greater the complexity of an entity, the greater the agency it will likely have. The more abundant agency is, and the more sophisticated agents are, the more creativity there is—which in turn increases the rate of the emergence of complexity.

The advent of self-reflective mind has yet again amplified the cosmos’s adjacent possibilities, even with the most elemental components. Humans mine metals out of the earth and use them to build thinking machines, use chemistry to enhance our industry and turn sand into concrete skyscrapers. We harness microbiology to ferment new foods, we corral animals to convert starlight to calories via their native ecological behaviour, for our exclusive consumption. Mind takes the emergent results of wild cosmological creative exploration and redirects them into ever more and new adjacent possibilities that, without self-reflective mind, wouldn’t exist. Of course, self-reflective consciousness also introduces new qualities that are purely unique to itself, like moral, philosophical and scientific perspectives and the subsequent adjacent possibilities that arise from these.

The increasing capacity of our universe to be creative is a fascinating point. For example, when the very first star formed there would have been: Space (lots of), Time (also lots of), Hydrogen, Helium and probably some Lithium (lots of these), Gravity and a bit of light bouncing around. In hindsight of knowing that these are the ingredients of a star, what else is there to do? So repeated occurrences of these combinations across millions of light years would often do exactly the same thing—form stars. The system constraints dictate few other truly evolutionary possibilities. However, the further you get into the history of the growth of the cosmos, adjacent possibilities explode. With biological life or self reflectivity, adjacent options are multifarious in the billions, the uncounted , inconceivable gazillions, instead of one dumb and (hindsight being a wonderful thing) obvious option—become a ever more dense cloud of gas. This is the greatest hallmark of universal growth—the growth in it’s capacities to be creative, the growth in it’s emergent options.

As agency increasingly gets involved in creative processes, the more they seem “directed” towards greater complexity. This has been misunderstood by the “directionalists” (of whom I’ll discuss more later) to be a fundamental property of evolution itself, an implicit directedness. This is one of the problems that has arisen from the initial development of the theory of evolution—it was discovered via biology in relation to species variation—and so is often considered to be only a biological phenomenon. But of course, by the time you’ve reached a biological level or threshold of creativity, evolution’s origin is buried amidst several layers or thresholds—each one of them amplifying the possibilities afforded to the previous level of creative possibility. So trying to clearly deduce what’s going on via biology is that much more difficult.

It is only with the great discoveries of 20th century science such as Hubble’s discoveries at Mount Wilson Observatory of galaxies and an expanding cosmos, the understanding of material evolution via supernova explosions (etc), that we have come to discover evolution’s origin is a cosmological one, not a biological one. It would have been much more convenient if we had discovered first the big bang, then universal expansion, then the evolution of matter and chemistry and then the evolution of life. But we didn’t, so for many, even though it’s not, Evolution is still mainly thought about as only a biological phenomenon.

Evolution’s origin (intro)

A reconfigured history of universal emergence

Download a free PDF of this article - requires email address. Privacy: We will not share your data

DownloadPART II

Reviewing and renewing conceptions of universal emergence

DARWIN AND WALLACE

As you may well know, the theory of evolution was the inventive conclusion of not one but two Englishmen and explorers: Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace. In Dover, England, March 14th 1831, a young Charles Darwin boarded the HMS Beagle for what would be a five year voyage of exploration. On that trip, during a visit to the Galapagos Islands, Darwin assembled collections of finches and mockingbirds from the different islands. He wrote: “Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one specimen had been taken and modified for different ends.”[Reference 3] Later, Wallace, using Singapore as his base spent 8 years (1854-1862) in what then was called the Malay Archipelago, exploring the islands and jungles and collecting specimens of the creatures he encountered. Surrounded by an endless diversity of species, Wallace inevitably renewed a contemplation of how on Earth such biological diversity could arise (he was already partial to an idea called “transmutation of species” which preceded evolutionary theory). He wrote in his autobiography: “The problem then was not only how and why do species change, but how and why do they change into new and well defined species” [Reference 4]. Wallace subsequently sent his latest ideas in an essay to Darwin who had been developing the same ideas on Evolution back in England for some 20 years, prompting Darwin to finally publish them, alongside the essay Wallace sent.

It’s important and interesting to note that the reason that Darwin and Wallace came up with their theories of natural selection was because of the stunning and incredible diversity of differences between otherwise very similar species. What they were preoccupied with was the prolific native creativity in nature. How could there be distinct adaption and difference, but also so much similarity between the differences. They were not looking at difference as complexity to which evolution is so often attributed as being about—but differences full stop. They were awed and fascinated by the prolific variation in the biological world.

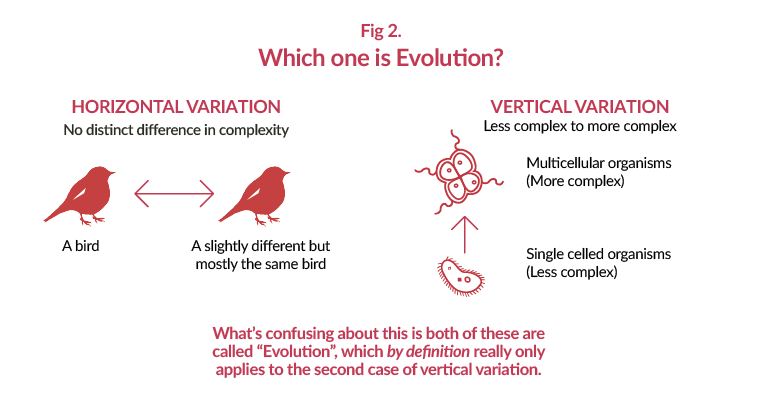

It’s not a well noted fact that Darwin’s original edition of The Origin of Species does not contain the word “evolution” anywhere (though it does contain the word “evolutionary”—“evolution” was added to the last edition released thirteen years later in 1872). It was not mentioned in his works until The Descent of Man in 1871. Apparently Darwin didn’t like the word used it because it was becoming common parlance [Reference 2a]. I find this an intriguing story, because so much of the discussion of evolution and it’s most famous definitions are about the “vertical” emergence of complexity, that is, for example, from single celled to multi-celled organisms and so on, as opposed to the “horizontal” change seen in Darwin’s collection of Galapagos finches, where there is no real difference in biological complexity.

It was the biologist Herbert Spencer who advocated the term evolution which meant “progress” or from it’s original latin “unfolding”. “Unfolding” has never meant “variation”—which is probably why Darwin was reticent to use the word in the first place. Using “evolution” to describe adaption and variation is a twisting and contorting of an otherwise perfectly good noun. Its not an abuse of the word so much as the point of view Darwin was espousing. Variation is creative and unexpected, it experiments and invents, but is not so unfoldy or progressive.

THE SEMANTICS OF CREATION

I suspect that because we’ve not really been doing it for that long, our vocabulary for discussing the subtleties of creation is rather limited and undeveloped. We need far more differentiated language with which to talk about these things more clearly. Lack of the subtle enough definitions can lead to glib thinking. In particular the term “Evolution” has started driving me a little nuts, and I’ve come to realise we need to talk about it’s definition, because “Evolution” has apparently come to mean two things: a) emergence of “vertical” complexity and b) manifest variation which—in terms of vertical progressive complexity—is horizontal, there’s no distinct change in complexity. It’s is confusing because most people use it to mean only the first definition and for good reason—“unfolding” or “progression” don’t really work as descriptions of horizontal variation (See Fig 2).

An interesting fact of any word beside it’s definition, is how it’s actually used and perceived by the users. There’s the original or dictionary definition of a word is one thing—then there’s the current subjective and social reality of how and in what context a word comes to be used. I personally don’t experience the word “Evolution” to ever mean the non-progressive emergence described by Darwin’s finches. It’s not commonly used to refer to non-progressive emergence that doesn’t result in complexity—only the emergence that does. For some people “evolution” means both. Well, God bless their cotton socks. But I think for the rest of us it’s actually quite confused. We clearly have always needed two words: one for the development of “vertical” complexity, and one for non-progressive emergence. I’ll come back to this in a minute with my suggestions on what to do.

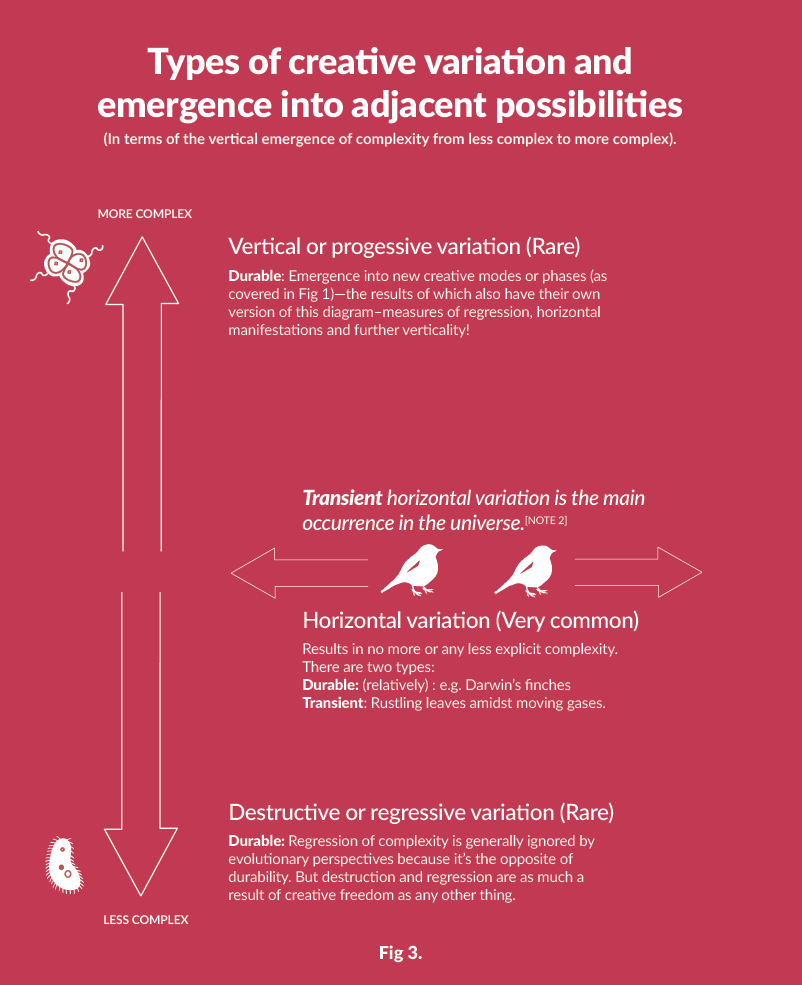

CREATIVE VARIATION VS EVOLUTIONARY COMPLEXITY

In my attempt to innovate a way thinking more clearly about emergence, I started by inventing two labels for different types of complexity: “hard” and “soft”. In this thinking, Hydrogen atoms bouncing around in a cloud in deep space will obey some kind of gaseous or fluid dynamic (I guess) and have some kind of complexity as a cloud but it is “soft”. Most of this freedom causes nothing at all except random movement, interaction, distribution etc. But occasionally there is the emergence of greater “hard” complexity—when the cloud condenses and compacts under the force of gravity to form a star. In this approach, that star is a “hard” emergence of complexity, as were the atoms in the cloud, but not the cloud itself, which is “soft”. Playing devils advocate to my own idea: I find these distinctions blurry and not helpful enough. On reflection I realised that complexity isn’t the right thing to focus on in the first place. I mean, Darwin’s finches weren’t manifesting more or less complexity in their differences, just variations at the same level of complexity. Thinking along this vein I’ve come up with a different approach that finally encapsulates my thinking on all of this: Durable vs Transient Variation (Fig 3).

All evolutionary manifestations occur via the process of variation. Free creative variation into adjacent possibilities is the fundament of, and the process of universal emergence. Variation is the normal daily life of the cosmos. This includes durable and transient variations. Evolutionary perspectives usually concentrate on the durable results, only. But in every free moment of the cosmos, the life of the cosmos is in motion. Earthworms munch on soil matter, leaves rustle, gases billow. Every transient non-durable moment of the cosmos is as much a significant part of it, as any durable development. But it is only the durable ones we seem to study. We have traditionally looked only at the durable results of emergence, such as species variation in Darwin’s finches, and ignore the main happening—the ever present creative freedom that is always present and that allowed them to emerge in the first place.

Figure 3 describes this in terms of the emergence of “vertical” complexity as described in Figure 2.

At any given moment one of three things can happen in terms of “progressive” or “vertical” emergence: a) destruction b) variation that doesn’t result in the progression or regression of complexity c) vertical or progressive emergence. Critically all of these three are the result of the ever present freedom to be creative into adjacent possibility. Also critically, all of these are some type of variation on what has gone before, some exploration or another of an adjacent possibility. They are all a category of variation. Of these, horizontal variations are main events in our cosmos. They can be either durable or transient, and the main occurrence of these two, the most common event in our cosmos is transient variation. Wherever you are reading this, transient horizontal variation is going on all around you. It’s the virtuous exploration of the creative freedom afforded to every moment of existence.

Amidst limitless freedom, the emergence of more complexity is an inevitability. Thus the emergence of complexity, or evolution as we define it is an inevitable but really secondary or tertiary side effect of universal freedoms and creativity. It is not the main occurrence. The main event is idleness, simple freedom, ever present newness and endless unknown potentialities amidst infinite adjacent possibilities.

It’s not possible to call a rustling leaf (transient horizontal variation) in the wind “Evolution” and be making any sense. Because either version of what’s commonly considered Evolution isn’t the key event that occurs or the reason any evolution actually occurs, I’m of the opinion that the “Theory of Evolution” should be renamed the “Theory of Universal Emergence” and Evolution should be talked about for what it is—not a process, but a view of the results of emergent processes—“The Evolutionary Perspective” which would be included as per Fig 3 into the Theory of Universal Emergence. This would lessen confusion and clarify thinking for everybody.

The main event is idleness, simple freedom, ever present newness and endless unknown potentialities amidst infinite adjacent possibilities.

PART III

The Directionalists vs The Scientist

One of the triggers for me to even write this article occurred upon reading the excellent book by Robert Wright, Nonzero [Reference 5]. The 19th chapter of the book is an extended critique on the work and ideas of the late great palaeontologist (and—in certain circles—infamous reductionist) Stephen Jay Gould. In particular Wright critiqued Gould’s book Life’s Grandeur—whilst Wright championed his own views on directionality in Evolution. I was fascinated and subsequently read Life’s Grandeur to find that in fact I agreed with much of what Gould was saying. Having described what I believe to be a robust and useful approach to the origin of Evolution, I think it’s a good exercise to run it through the arguments and views of both Wright and Gould to gain some perspective on the relevance of it as a point of view.

Ding! Round one

The Scientist: Stephen Jay Gould on Evolution

What I learnt from Gould is the general perspective that’s know as “progressionism”, in the industry of Darwinian palaeontology and the like is not well received, and Gould spent this entire book explaining why. Gould was a Darwinian through and through, and that meant he had a healthy regard for the original theory of natural selection from which this whole fuss arose, and the essential key that I have been rabbiting on about: variation is key to understanding evolution.

Whilst in my opinion quite dogmatically confining his interest in Evolution to biological subject matter he otherwise clearly identified variation as a key factor in evolutionary emergence in statements like: “...trends to improvement [are] best interpreted as [the] expanding or contracting of variation” or “Natural selection talks only about “adaption to changing local environments”; the scenario includes no statement whatever about progress—nor could any such claim be advanced from the principle of natural selection.” and also, “from a necessary beginning at the left wall, random motion of all items in a growing system will produce increasingly rightskewed distribution. Thus...the evidence for progress—the increasing complexity of the most complex—becomes a passive consequence of growth in a system with no directional bias whatever in the motion of it’s components.” Later in the same book Gould cites several empirical studies concluding there are no innate tendencies for progress in evolutionary process.

As quoted above, a core point of Gould’s is his concept of a “left wall of minimum complexity”. Gould describes this wall as being the absolute minimal amount of complexity that a living thing could possibly have and still be classified as “living”. To the right of this wall exists all greater complexity in the biological world. His thinking is simple: if the microbiological world is relatively close to this left wall—which it must indeed be: the only way is, more or less, up. Not in a direct line: his simple point is random development via variation will eventually, naturally move, towards, along, and sometimes away from this wall. This conceptually matches various forms of variation I mentioned earlier: regressive (towards the wall), horizontal (along the wall) or vertical (away from the wall). No “progressive force” is required for the eventual emergence of complexity.[Note 3] Gould compares this phenomenon to the paradigm of the “drunkard’s walk”. A drunk, kicked out of a bar, given enough time to randomly stagger about, will eventually find the gutter after exploring many places in between, including the wall she starts at.[Note 4]

I think we can expand this concept to apply to all of creation, not just the biological world. At any given moment, the entire universe in is it’s latest current state. From this current state of complexity all adjacent possibilities can be explored via free variation, either—in terms of emergence of complexity—regressively, horizontally or vertically. (Fig 3). From this point of view, the emergence or evolution of complexity really is a tertiary side effect of freedom for creative variation or as Gould put’s it, the “passive consequence of growth in a system”. Atoms can smash themselves back into sub atomic particles (regressive), laze about on the wind (hozizontal: the main thing that happens), or become included into molecules (vertical).

In other ways Gould’s ideas can seem off-kilter and bizarre. I find him to be quite an exasperating writer in that he can make profound sense and complete nonsense in a single page. He was genuinely of the opinion that because bacteria are the most adapted and resilient life form on Earth that they are the pinnacle of evolutionary unfolding and have made the most progress! Whilst bacteria are truly amazing, I think many would disagree with this position and say that in fact it is Human civilisation that is the pinnacle of evolutionary unfolding. He arrived at these conclusions by only looking at biological natural selection as being the determinate of what is most evolutionarily worthy. Thinking only about natural selection in the biological world leads to this kind of erroneous thinking. This is a perspective sorely lacking a cosmological reference point for thinking about what evolution really is. It’s also quite disturbing in it’s refusal use any other form of appraisal, including basic common sense. I think an 8 year old could confidently tell you that humans are more complex, extraordinary and “progressed”, than a bacterium.

Otherwise, I’ve found it particularly encouraging that I can find much to agree on with such a well known reductionist and scientist, because—as I will discuss through the rest of this series—whilst I am very interested in a very anti-reductionistic and possibly “spiritual” view of a definitely meaningful cosmos—I do strongly feel that any approach must correlate with good and hard scientific data and the subsequent thinking. By correlate I don’t mean duplicate—just not be contradictory. Ideally, all correct points of view should be able to mesh together to form a truly scalable, robust and useful perspective.

Simultaneously, Robert Wright’s attacks on Gould’s approach only highlighted for me the problems with what I call the “Directionalist” approach.

Ding! Round Two

THE DIRECTIONALISTS

“Directionalists” is a term I’ve invented to describe those who believe the evolution of the cosmos has been “directed” by an “evolutionary impulse”, or as S.J.Gould calls it: “the directed thrust of causality”, towards a general or specific goal. The official terms for it is “Orthogenisis”. They include for starters Robert Wright (at time of publishing Nonzero), fellow Australian philosopher John Stewart (in his book Evolution’s Arrow, which is also in part a riposte to Gould’s writings on the topic of Evolution) and the Evolutionary Spiritualists such as Ken Wilber, the late Barbara Marx Hubbard and Andrew Cohen. In their view, evolution has a teleology: a goal and purpose. Their catchphrase is often enough: “Evolution is directional”.

Do you find that statement odd? “Evolution is directional”? Surely that can’t be a serious statement, can it? Everyone knows evolution is directional—that’s what the word evolution means....isn’t it?

Well, yes.

How could sensible, best selling grown adults come to passionately advocate such an obvious thing? I’ve come to realise what it is. It’s because there are some scientists who genuinely believe there is no distinct progress in Evolution! As I mentioned earlier the exasperating S.J.Gould had genuinely odd ideas about what progress in Evolution actually is. He shares these ideas with other scientists who really do only think about the theory of evolution as being only about variation by natural selection. Any ideas or values of the broad progress of universal emergence just don’t come into it. This has understandably worked the directionalists into a complete lather and they all cite disagreement with Gould’s work.

To be clear: I unequivocally support the fact of general progress in the unfolding of the cosmos, as I described in Figure 1. It’s the reason we all find the Evolutionary perspective so amazing. The advent of biology from chemistry, for example, is clearly a progression in fact and in value. Biology is more complex, more organised, more dynamic, more beautiful. Pick any reference, there’s clear progression. Helping clarify things here, directionalist Steve McIntosh, writing in his Integral Consciousness and the Future of Evolution [Reference 8] quotes well known scientist and materialist E.O.Wilson: “If we mean by progress the advance toward a preset goal, such as that composed by intention in the human mind, then evolution by natural selection, which has no preset goals, is not progress. But if we mean the production through time of increasingly complex and controlling organisms and societies...then evolutionary progress is an obvious reality.”

However, almost all directionalists take the simple point—that there has been progress in universal emergence—and confuse things by insisting that the reason for progression must be because of some kind of orthogenic impulse and universal purpose. Because the Directionalists don’t ever clearly separate the two concerns, I tackle all points here as regarding an orthogenic impulse.

My issues with the directionalists in a serial list (my apologies in advance—some of this can be a little boring):

a) Misuse of plain english demonstrate their poor thinking on the topic.

“Evolution is directional” is a plain silly thing to say. It’s the same as saying “Progression is directional” or “Unfolding is directional”, which is more or less the same as saying “Direction is directional”. Nothing wrong with saying that in passing per se—but this is their strap line, their war cry, their core position: [Direction] is directional!”. Well, duh. I could appreciate it if there was some confusion around the definition as I covered earlier—but there’s no distinct attempt to clearly qualify usage in either Wright’s or Stewart’s works, so what gives?

When people aren’t using plain english clearly, it’s a sign of poor thinking. In this vein, Directionalist’s commonly talk about Evolution being a thing, with properties and possessions (Erm...just for a moment, ignore the title of this article!). Statements like John Stewart’s: “Evolution has organised molecular processes into cells...” make no sense. Evolution hasn’t organised anything. Evolution is not a thing, it’s our view of results of creative emergence.

b) There is no evidence of an orthogenic impulse in evolutionary emergence.

Probably the most important of all points on this topic: Apparently it just doesn’t work like that! S.J. Gould cites three studies in Life’s Grandeur (McShea 1994 studied evolution of complexity in vertebrae and later fossil teeth in mammals, Boyajian and Lutz 1992 studied complexity in Ammonites) that found no native trend to complexity.[Reference 2b]

c) Feedback loops are no proof for an embedded cosmic directionality

Wright and Stewart both make the same mistake of starting an analysis with biology and then culture as a means to deciphering the mystery of evolution. For example, Wright cites feedback loops, such as interspecies arms races [Reference 5] as being a driver of emergence of more complexity—giving biological evolution a clear directionality.

In this way biological evolution does have directionality, but not really. Remember the cosmos moves through “creativity thresholds”. Each time that happens creative options increase dramatically largely because of increasing agency that seems to correspond with increased complexity. The more agency there is, the more directed developments can get. Once you have biology and complex biology there is a lot of agency around. Agency means things can be directed by the agents whether be the selfish gene or the agency of an individual. That agency can give the appearance of direction in that emergence—but it is really agents taking advantage of the available freedom to act. The directionalists, in failing to identify the core reason for evolution (freedom for creative variation) miss this point and get themselves confused. Biology is already a few creationary event horizons into things so it’s harder to discern the base reasons. It’s helpful to remember that evolution was happening well before biological life ever arose, and indeed was the reason it could be, erm, arosed. The directionality Wright spots is happening, but it is an emergent phenomenon resulting from billions of years of creativity and the resulting agency, not an implicit mechanism of the nature of universal emergence. Actually, this emergent directionality is yet another an example of how creative options become ever more amplified. In Nonzero, Wright doesn’t address pre-biological evolution much at all—which in part is probably why he’s missed the mark. The pre-biological source of evolution is a harsh austere fact that demands a straightforward, scintillating answer. Universal creative freedom is that answer and evolution’s “origin”.

In Nonzero Wright’s writing on feedback loops subtly slides into discussion on the rapid expansion of brains in monkeys and hominids as yet another argument for directionality: but this is of course the latest and maybe most significant “creativity threshold” of them all: mind—or more specifically (in the case of hominids) self-reflective, self-aware mind. Post-biological explosive creativity of mind creates even more powerful feedback loops. In this case the more intelligent and capable the individual’s mental capacities, the more likely it is to produce offspring, thereby creating a powerful feedback loop in the development of the genetics in that species. Mind now becomes a factor in universal emergence—directly impacting biological systems in a clear feedback loop. There is more focused directedness because there is now more powerful agency to make use of the same universal freedoms that have been present for some 13.6 billion years.

At the point of self-reflective agency, then there really is a directional departure, but driven by the will of individuals, not any universal process. This is why mature self-reflective civilisation may be of great significance. We can deliberately give to the cosmos something it may never have had—determined direction. I like this statement from Eric Jantsch: “...the whole universe concentrates to an increasing extent in the individual. The individual, in turn, increasingly assumes integral responsibility for the universe in which it lives.” [Reference 6b]

d) Cooperation isn’t proof of directionality

John Stewart and Robert Wright are both big on citing co-operation as being proof of directionality. But here again in my opinion they have missed the forest for the trees—partially because again they have started trying to untangle this issue with examples from the biological world and the cultural world of homo sapiens.

With increasing agency there is increasingly the option for agents to self organise into larger and larger units. These clearly have a creative advantage as they have unique and new properties that they would not have as constituent parts. eg atoms, molecules, living cells that can move and adapt, amoebas, rabbits, economic nations such as the EU or US, and so on. Clearly cooperatives have distinct advantages in terms of robustsness, rigour and size. Robert Wright’s entire book Nonzero is about the advantages accorded to individuals and collectives that play non-zero sum games (where both parties benefit). It is true and fascinating and important, but it doesn’t mean anything fundamentally about why evolution happens. There are also trends to diversity, and trends to greater individuation. Trends to everything can result from rampant universal scale unbridled creative emergence and exploration of adjacent possibilities. I think the entire discussion would benefit by pausing before jumping to label any systemic theme a directional property of universal telos or purpose.

Directionalists intimate that because it’s such a clear trend to co-operation, we can then extrapolate general futures that will be full of further co-operation. On that I agree. On this topic, John Stewart is of the opinion that “The potential for increases in the scale of cooperation in this universe will end only when the entire universe is subsumed in a single, unified cooperative organisation of living processes. It will end only when the matter, energy and living processes of the universe are managed into a super organism on the scale of the universe.” [Reference 7b] Sounds good to me. (*High five*).

e) Directionality is required for Human intelligence to emerge

Also there seems to be a clear concern that if there is not an implicit directionality in evolutionary processes, there would not be a guaranteed emergence of something like a Human-like level of self reflectivity. To me it seems, once there is something like biological life, it’s inevitable that some forms of consciousness will emerge. It doesn’t guarantee self-reflectivity. But when you see how much intelligence there is in squids, dolphins, monkeys, elephants etc, not to mention our own, it does seem like an eventual probability, given enough time and the right circumstances. Hindsight being a wonderful thing, it’s clear now that some form of biological life was in the magical future of our early cosmos. That being the case, it seems that self-reflectivity was too. But, we live in an unrepeatable creative cosmos, that’s unpredictable and free. What if that boulder that killed the dinosaurs started it’s trajectory a millimeters to the left?

In the end, discussion like this seem like they can only be resolved by understanding why the universe exists at all. Once it does, and it’s free, this stuff or something very like it, is going to happen and directionality isn’t required. I’m obviously not going to be able to tell you why the cosmos exists, but we’ll come back to this.

f ) Few agree with them

As a way of winning an argument, claiming you have more supporters than the other guys really is the worst possible approach—but I’m going to do it anyway. The mainline for some time now has been there is not a native progressive tendency built into evolutionary processes:

Charles Darwin didn’t think there was any progressive tendency in evolution. Darwin wrote to the palaeontologist Hyatt: “After long reflection, I cannot avoid the conviction that no innate tendency to progressive development exists.”[Reference 2]

Eric Jantsch in 1980 wrote: “The directedness of evolution now may be understood post hoc as the result of the interplay of chance and necessity; necessity is introduced by the systems constraints which are themselves the result of evolution.” [Reference 6a]

g) The presence of an “impulse” or “drive” causing evolution would mean there cannot be real novelty or freedom.

A “drive” to something specific indicates pre-knowledge of what can or should happen. If it has a preset goal, there is no such thing as freedom. This is suspect in at least describing a cosmos that is already “fixed”. Surely that’s the worst possible option of all the cosmoses one could have? It doesn’t seem to correlate with the wild freedom this one exhibits.

This is a key criticism of the work of Alfred North Whitehead, who was actually keen on the novelty present in creation. He posited that evolution was caused by the “gentle persuasion of love”. A love he called Eros, that desired always more perfection. It’s a beautiful concept. However, for something to want something that doesn’t exist implies pre-knowledge of what should exist. If you have that, you don’t have a free cosmos. Which we do. Ours is also apparently not developing from any orthogenisis, which is what Eros is, so, unfortunately, it appears he was wrong. [Note 6]

DING! Round three

THE EVOLUTIONARY SPIRITUALISTS

Evolutionary Spiritualists are also Directionalists. Evolutionary spirituality (ES), in it’s ideal form is an attempt to marry mystical, religious and spiritual understandings with scientific world views to create an all encompassing perspective that comprehensively explains our cosmos. In the context of an evolutionary understanding of cosmos, evolutionary spiritualists have become proponents of the evolution of consciousness as being the point of all religion and spirituality. In this context, Evolutionary spiritualists aspire to provide a new context for living with meaning and purpose. Right across the board, evolutionary spiritualists advocate the presence of an “evolutionary impulse” that “drives” evolution forwards.

As previously mentioned, if we want to architect new contexts for living with meaning and purpose in the third millennium—including those view that aspire to have a mystical or spiritual aspect—I strongly feel we need perspectives and approaches that mesh extremely well with good hard science. Not to say I’m a strict reductionist or materialist, but ignoring good science is dumb. I particularly take issue with the the directionalists in the “Evolutionary spirituality” movement who have consistently and exactly not done this. They have taken the entire concept and understanding of evolution as a base to their outlook and then consistently propagated the idea of a “driven” emergence of the cosmos that has no basis or reference to any science whatsoever. They disregard the science they are claiming to base their approach upon, resulting in a view that is misleading and useless. In my opinion this approach has spectacularly failed and damaged any movement to create a post-traditional and post-scientific (that means based upon or correlating with good science)—but still “spiritual” perspectives on our cosmos that can be used to generate new forms of meaning and purpose in the third millennium. This article is, in part, an attempt to repair that damage, and set us back on course.**

It’s entirely possible that there is some profound subtlety in the nature of things that’s hard to perceive, something that makes the “evolutionary impulse” argument correct. If there is, the Evolutionary Spiritualists must correlate this information with formal studies. In doing so they would demonstrate the very real gap in data that proves their approach has validity. I think they have failed to do this because their entire approach is glib and incomplete.

Critically, we should ensure any new context that we should choose for meaningful and purposeful living should be well and truly free of any dogmatism. For example, the bible says the Earth was created 6000 years ago. That does not correlate with hard empirical science, so it’s out. I feel ridiculous even having to say obvious things like this but this is the situation the Evolutionary spiritualists have created! Any approach must be passionate about the truth of reality, no matter where that information comes from. That means being willing to concede positions when they are unequivocally shown to be incorrect. For it to be scalable and useful, this must be the essential character of any third millennium “theology”. As I always understood it, this was the original goal of the evolutionary spiritualists, which makes their failure on this point even more disappointing.

Evolutionary spiritualists can make amends here by changing the approach just slightly—and stop insisting there is a orthogenic impulse behind evolution. Whilst they insist the universe is the way it actually isn’t, in scientific fact, their views are simply unusable and it undermines their entire approach. If you are going to contradict good data—make a clear case as to how your version works.

Ultimately, I believe there is only one correct version of how everything ultimately works that we can only aspire to understand.

HARD OBJECTIVITY, HARD SUBJECTIVITY

Would you agree the cosmos is beautiful? When you see those spiralling galaxies in Hubble Space telescope images, can you deny that they are awe inspiring? If you ask a scientist to reduce beauty to mathematical equations, or some kind of physics they won’t be able to do it. Beauty cannot be quantified by a reductionistic or materialistic tradition of science. That’s no small point. Beauty is clearly a critically important appraisal of the nature of our cosmos that can only be accessed via our personal intelligence for life. No physics equation or measurement of pupil dilation or heart rate will be able to replicate the personal awe you may have experienced and know to be profoundly meaningful. These subjective qualitative understandings are generating real and important information, or, to use technical parlance: data. It’s important and useful information. Whilst I have been saying we need to correlate all views with “hard science”, I’m also of the opinion that we need to qualify our views as best we can with— for want of a better term— “hard subjectivity”.

This can potentially include the correct parts of “data” generated by generations of sages over the millennia of human history in many spiritual or religious traditions. Sages throughout the ages have referred to discovering a non-dual fundament or living “ground of being” as the essence or foundation of our cosmos. That place where one can sink to when in the deepest of meditation. They cite this ground as being an elementary part of the construct of the cosmos, if not it’s origin, essence and heart. Often enough, the consistency between traditions or schools and some of these descriptions is compelling. There are vast quantities of this “data” that we shouldn’t ignore casually. Especially when no-one really knows whats going on here.

Of course, with subjective experience, being scientific about it is problematic. At the turn of the century American pragmatist philosopher William James developed a method he called radical empiricism which attempted to evaluate subjective experience in the same way as sensory empirical data normally used in science is evaluated. There’s at first an experience of some kind, but it’s interpretation is everything. Due to the variability between individuals in cognitive, emotional, rational and subjective intelligence, and their cultural context and background, it’s extremely difficult to correlate subjectively generated information. Also, when it comes to mystical experiences: by their very nature they are an experience of something not containable by thought. One can attempt to describe the experience afterwards, but the description is never the experience itself, and still subject to interpretation.

Hard subjectivity is of course the promising alter-data that Evolutionary Spirituality has so far failed to reliably provide. Despite that, I think we need to continue our efforts to include this information in our quest to understand everything. I don’t believe the approach I’ve argued here to how the universe has emerged necessarily contravenes any existing data, from all sources, which is encouraging.

And it’s a knockout!

THREE CHEERS FOR THE DIRECTIONALISTS, ACTUALLY

In his book Evolution’s Arrow, Directionalist John Stewart acknowledges there has been no evidence of directionality: “...progressionists have been unable to identify any plausible evolutionary mechanism that would continually drive progressive change along some absolute scale” [Reference 7a]. Considering the extensive study of Evolution over 150 years this is no small point. Evidence is kind of important when you are making grand sweeping statements about the nature of infinite existence. Meanwhile, the ever present creative freedom all around you as you read this is self evident, isn’t it?

Again, I’m not against an argument for a universal purpose behind creation. It’s just that the directionalists aren’t making any sense. That doesn’t mean they are wrong in their aspirations—it just means they are wrong so far. Anyone who repeatedly and firmly states that [direction] is directional is already off to a bad start. I think what all these “direction is directional”- ists are trying to communicate is what they feel in their lumpy, linguistically malformed hearts: they have found the results of the evolution of creation to be an awesome, stunning, beautiful phenomenon worthy of the attribution of great meaning and importance. I agree. But that doesn’t mean the process itself can automatically be attributed with an embedded purpose. Your personal meaning does not equivalate to everything else’s purpose. What’s meaningful to you is meaningful to you. That doesn’t mean there is a purpose present or that things are therefore inherently purposeful or purposeful in the form of a directed unfolding. I don’t want to say they aren’t purposeful, I just want to point out that’s not a logical step.

Simultaneously, I suspect the Directionalists are worried that if there isn’t inherent meaning via some embedded intention in evolution, the cosmos cannot be seen in any way as “spiritual”, or in some way based upon some kind of force beyond a purely reductionistic and material cosmos. By championing the idea of a directed evolution, the theory of evolution doesn’t get to suck every last drop of soul from creation. In the context of positions held by neo-Darwinists like S.J.Gould, that’s an understandable concern. However I don’t think incorrectly attributing cause where there is not is a way of resolving this. If there is proven working scientific contradiction to a point of view, that view is almost undoubtedly incorrect.

I think this perceived worry of a dead matter-only cosmos is misplaced. It just requires a little more creative guesswork and some better thinking and investigation to conceive of how the cosmos can be both divine whilst it’s emergence is essentially unguided. On that note, Panpsychists like Phil Goff are providing new perspectives on the nature of matter that are enticing and provide new avenues for exploration here.

PART IV

The beautiful mysteries

As a starting point, I like this point of view of a free creatively emergent cosmos as it is robust, understandable, accessible, scalable and doesn’t need to intrude upon or exclude more fundamental mysteries in order to be profoundly helpful. Simultaneously, I’m left with many more questions.

Amongst other things, I am a tennis player and a musician, and have always been amazed by the nature of the creative act—as a player utterly focused upon the ball rapidly approaching me (when I can muster it) I will find myself doing things with my body I didn’t know I could do or was going to do, so creatively that it’s truly astounding (to me, that is: to to others I probably look like a man with bad sports fashion making a terrible mistake). As a musician, chords and notes I’ve been playing my whole life will suddenly become a piece of music out of nowhere. In these acts there is the intelligent leap into adjacent possibilities but here is also something else. There seems to be a mystery at the heart of the creative act when we go beyond ourselves—something comes out of nowhere. Why? Is that just the nature of creative freedom—my free agency at work self-organising and self-creating— or is there something more to it?

Also: Why is everything so beautiful? Is beauty a virtue of existence itself? It does seem that the cosmos has become more and more beautiful as it has become more complex and diverse. In the evolution of life, it could contentiously be argued that more complex organisms are more beautiful. Whilst, they are all inherently beautiful, it seems to me the Dahlias in my garden are more beautiful than the mushrooms in the lawn, and the young black cat that has been visiting recently is more beautiful than the Dahlias. The cat is also more beautiful than any individual of the frog army that emerged from my pond in the spring. Integral philosopher Steve McIntosh wrote: “Cats, for instance, are not just more complex than frogs, they are also more graceful, more refined, more elegant, and more beautiful.”[Reference 8]. For the sake of interest, I think it can be added that the subjective consciousness of a cat is likely more subtle than that of a frog, with more subtle understanding of itself and the world around it. (Apologies to any frogs who may be reading this). The directionalists are right to be excited about the progression we can see in these developments.

Where does that leave us? I don’t know, but it seems critical that a contemplation of the “facts” of beauty, and increasing subtlety be a fundamental parts of any full appraisal of our creative cosmos.

You may have noticed I very conveniently start my explanations after the dawn of existence—after the explosion that lead to rampant multiplicity of subatomic particles condensing out of a dense plasma with brilliant flash of light about 300000 years after the big bang. After the fundamental components/laws of gravity, space, time and light have emerged. Convenient in that by doing that I haven’t explained what the hell is actually going on here, just some of what is going on.

Another of the great mysteries: Why is our cosmos apparently fine tuned for the emergence of life? Physicists have noted that if any of quite a number of different forces and constants of the cosmos were a slightly different value, life would not exist. For example, if the strong nuclear force was 2% stronger, there would be no hydrogen in the cosmos, which means no stars, which means no chemistry or life. If that same force was 5% weaker, hydrogen would be the only element in the cosmos. There are similar results when tweaking many other constants, like gravitational force or masses of atomic quarks etc. This is sometimes known as the Anthropic Principle—but I think it’s been mis-named. I think it should be called the Creativity Principle, or something like that, because it appears the cosmos isn’t fine tuned for life—it’s fine tuned for optimal creativity. Why?

As you read this, I invite you to consider the space around you. Not the objects in the space you are, just the actual space itself. We can’t see it, and it’s so fundamental to our existence that we take it for granted—but in the beginning, it didn’t exist at all. There was no such thing as space. There was nothing (we think). Whatever principle is behind existence, it clearly favoured there being something over nothing at all. It may be impossible for our feeble minds to understand how such a phenomenon as space could be created from nothing at all, but the fact that it was indicates a distinctly “pro” attitude toward creation. It’s then no surprise that creativity where something comes from nothing permeates the very nature and character of existence. If anything, the soul of creation may be this elementary creative principle—the love for existence itself—without any specific idea or direction, just as long as there is not the bondage of absolute zero, of nothing at all.[Note 5] A love for free existence itself, but acting as a support, a container, but not an active component.

There can be meaning and purpose in this. Why does there need to be any more purpose than this? Creativity is always directional in that it’s always creative. Something new happens. That does not mean something evolutionary happens. It just means something happens. Whatever is going on—our cosmos clearly favours something over nothing. Interestingly, a something that is static, that can’t create or emerge independently, is not a very interesting something. It’s almost as good as nothing at all. But a something that has as it’s essence the love of something over nothing, a creative principle in it’s very fibre, a freedom to create and manifest on it’s own, now that’s a something worthy of creation.

Whatever the reason, this is the exquisite cosmos we live in—endlessly unfolding into a future of unbridled, undiscovered, unfettered potential for something.

- Note 1.

-

Whilst some molecules may be as or less reactive than some atoms, the diversity of molecules in size and type that can be created by the periodic table of the elements is vast, making the advent of chemistry in the cosmos a distinct macroscopic threshold of creative potentials. Go to reference in main text

- Note 2.

-

It’s tempting to say the freedom for any potential variation is the main event, but because apparently there’s no real perfect vacuum in deep space (because of cosmic radiation and other things like gluon fluctuations) most if not all of the cosmos is in a state of transient horizontal variation at any given moment. All space is constantly expanding too, supposedly. Go to reference in main text

- Note 3.

-

Gould’s wall idea raises another interesting point. Life cannot regress beyond a certain point and be called life. The same can be said for molecules, and atoms. They contain constituent parts and can regress back beyond a minimum wall of complexity in each of their own realms by being destroyed—at which point they are no longer classifiable as atoms or molecules. Interestingly in the same way life would not want to do this—it’s not in the nature of atoms or molecules to destroy themselves either—meaning that upon their emergence and due to their nature, it appears there is a native preference for horizontal or vertical variation over regression. They have a robustness that makes them so prevalent and successful. This could be seen as a thin grasp for an argument for directionality. Either way, it’s a testament to the pragmatic robustness of those phases of emergence. If they had a natural tendency to destroy themselves it would be be more difficult for complex emergence to be based upon them. This also possibly supports Rupert Sheldrake’s concept of morphic resonance. Whilst on the topic of Morphic Resonance in the notes here—I was looking for somewhere to crowbar it in— it is left in tact by the conepts of this article as it fundamentally relies on the novelty of free creation. It regards the possible/potential patterns that form after emergent creativity. Go to reference in main text

- Note 4.

-

On the topic of feedback loops in interspecies competition/ relationships: In Nonzero, Wright rightly points out that Gould doesn’t mention feedback loops when talking about the stumbling drunk. I agree that the stumbling drunk metaphor is not, in the end, the best way of making the key point (that evolution happens because of non-directed free variation). Fair enough. But in the end directionality that emerges from feedback loops is emergent from increasing agency, and is not implicit to the process of evolution. The stumbling drunk metaphor aims to describe only the fundamental reality of universal creative freedom for variation as the fundament of any subsequent emergence, but is confusing as it uses a biological organism (which can create feedback loops) to do it. Go to reference in main text

- Note 5.

-

By the way: This approach could be a basis to refute the “problem of evil” that some have raised in philosophical thinking. The creative principle behind existence had enough on it’s plate, so standards were of a certain focus. However, choosing something over nothing at all could be seen as having has an essential morality to it. Go to reference in main text

- Note 6.

-

Carl Hausman pointed out: “...if eros were the exclusive dynamic principle, of a process, that process would not be creative, for it would not allow for a change in the subject as determined by its initial direction. ... Novelty in the intelligible structure of the outcome would be absent.” [Reference 9]. Another kind of evolutionary love called Agape was proposed by extraordinary 19th century American thinker Charles Pierce in his essay Evolutionary Love. I can’t see it being required in order for emergence to happen, so I currently also reject this idea using Occam’s Razor: the simplest explanation is often the best. Ken Wilber and others claim that evolution is caused by both kinds of love, Eros and Agape. Agape being enthusiastically crowbarred in to solve the problems and limitations in the concept of Eros. Go to reference in main text

- Reference 1.

-

Reinventing the Sacred, Stuart A. Kauffman, Basic Books, 2008. Go to reference in main text

- Reference 2.

-

Life’s Grandeur: The spread of excellence from Plato to Darwin, Stephen Jay Gould, 1996 (2005 Edition), Vintage a) Chapter 12, p137, b) Chapter 14, p210 Go to reference in main text

- Reference 3.

-

Voyage of the Beagle, Charles Darwin, 2nd ed., (1845), p. 380. Go to reference in main text

- Reference 4.

-

My Life, Alfred Russel Wallace, Chapman & Hall, 1905 p. 361. Go to reference in main text

- Reference 5.

-

Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny , Robert Wright, 2000, p270 Go to reference in main text

- Reference 6.

-

The Self Organising Universe: Scientific and Human Implications of the Emerging Paradigm of Evolution, Eric Jantsch, 1980, Pergamon, a) p8, b) p16 Go to reference in main text

- Reference 7.

-

Evolutions Arrow: The Direction of Evolution and the Future of Humanity, John Stewart, The Chapman Press, 2000, a) p8, b) p37 Go to reference in main text

- Reference 8.

-

Integral Consciousness and the Future of Evolution, Steve McIntosh, Paragon House, 2007 Go to reference in main text

- Reference 9.

-

Eros and Agape in Creative Evolution, Carl. R. Hausman, Process Studies, pp. 11-25, Vol. 4, Number 1, Spring, 1974 Go to reference in main text

Evolution’s origin (intro)

A reconfigured history of universal emergence

Download a free PDF of this article - requires email address. Privacy: We will not share your data

Download